By Jim Farrell

Ah, after our long drawn-out winter, now is the time too head down to the boat and begin our summer of water adventures. Some Columbia River sailors will head out across the Bar and head north or south while most of us with just a little time will cruise the mighty Columbia, its tributaries, and backwaters.

Close to home, you can take a leisurely sail along the floating homes moored in protected waters, envisioning what it’d be like to live on one and enjoying fishing and other waterborne activities on your doorstep. The thought of being able to drop a line into the water to catch an evening meal, or just sit on the deck; to sip a favorite beverage and watch the river life float by, brings a calmness to one’s soul.

Still others with a little more imagination, enhanced by a dense fog that wraps its wispy moisture around their boat, may for a moment, if they try very hard, hear voices from the past. From the “River Rats” who eked out a living on the river and lived on the water. Some of their old houseboats can still be seen today….

Most were fishermen, loggers or worked on tugs towing the many log rafts. Others of the fairer sex worked alongside their men. (If the stories this writer has heard are correct, some ladies worked out of houseboats or barges in the world’s oldest profession!)

The first recorded floating bordello that this writer could find was operated by Nancy Boggs in the 1870s. Nancy would move her whiskey barge depending on local market demand between Linton and Oregon City. Portland was then three cities: Portland, East Portland, and Albina, each with their own government, set of liquor laws and police force. The solution that Miss Boggs and other “whiskey scows” devised was to anchor in the middle of the Willamette and have boatmen row your clients to you. That way they didn’t have to pay whiskey taxes to any city.

Oregon’s first Prohibition law passed in 1844 and due to its unpopularity, it was repealed in 1845. Other efforts came and went until 1919 when Oregon passed another Prohibition law. These on-again, off-again laws made liquor smuggling from Washington a great way for the ‘River Rats’ to make a living.

In 1922, when Prohibition became the national law, it presented Canadian smugglers with a golden opportunity to fill the holds of small cargo ships with booze, sail down the Washington coast and heave to 12 miles off the Columbia Bar in international waters.

They would then rendezvous under cover of darkness, with small, fast launches called “rumrunners.” With both vessels rolling in the swell, the Canadians would lower crates of booze down to the local crews, who would quickly stack as much as they could carry, speed away cross the Bar, and upriver.

Once they reached a remote pre-arranged spot, often on Sauvie Island or the Multnomah Channel, they’d pull in, unload their illicit cargo. Then they would turn around and head back to the mouth of the Columbia. If the coast was clear, they would cross the Bar and load up again, until the ship was empty.

Portland and the Columbia had always had a special mercantile relationship in illegal cargoes with British Columbia. In the 1890s, merchants in Vancouver and Victoria partnered with certain shady Portlanders to import enough opium to supply all the Chinese communities on the West Coast. The smuggling routes were time-tested, and the smugglers were well-trained; Prohibition was just a case of bringing in a different cargo.

This made for some frustrating times for Prohibition agents and the Coast Guard, because they couldn’t touch the ships in international waters and the individual launches were small potatoes and usually too fast to catch.

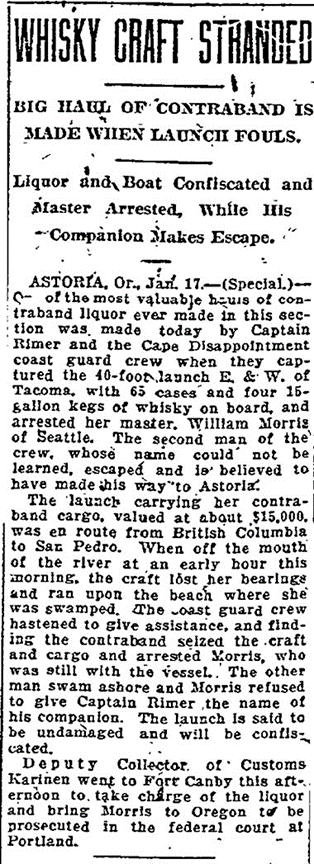

An especially interesting news story from the January 18, 1922. Portland Morning Oregonian announcing the capture of a 40-foot motor launch which lost its way in the pre-dawn darkness and ran aground at the mouth of the Willamette River while ferrying booze to Sauvie Island.

Then again, on February 3, 1925, as things sometimes happen, the S/V Pescawah, out of BC with its load of illegal spirits was waiting off the Oregon-Washington coast in a gale, when she heard on her radio that the steam schooner Caoba had washed ashore on the Long Beach peninsula, five miles north of Ocean Park, WA. She had been outbound from Willapa Bay loaded with lumber. Her propeller shaft had broken, and she began taking on water.

Soon she was only staying afloat thanks to the buoyancy of her cargo. The order was given to abandon ship, and two boats were put over the side. For 38 hours, the two boats were tossed around by the heaving seas. Finally, one boat was picked up by the tug John Cudahy, but the other boat was listed as missing with ten souls aboard.

Captain Pamphlet of the Canadian ship, Pescawha was laying off coast waiting for the rum runners to return. He had heard about the wreck on the ship’s radio and began plotting the wind direction and currents to figured out where the lifeboat might now be. With all good intentions, the crew of the Pescawha sailed inside the 12-mile limit and found the boat, rescuing all ten of the men. They took their lifeboat in tow, then pressed on full sail and headed due west.

Unfortunately, the Coast Guard cutter Algonquin had also plotted the drift of the lifeboat, saw the black schooner, gave chase at 16 knots, and boarded her. They arrested the ship, cargo and crew and brought them all back to Astoria. Besides the survivors of the wreck, there were also 1,200 cases of booze stashed in the Pescawha’s hold.

When they arrived at Astoria, they were greeted by a cheering crowd — including the rest of the Caoba’s crew. After all, it was only with skill and good luck that the Pescawah found the tiny lifeboat bobbing in the sea; if Pamphlet and his men had stayed in safe waters, the Coast Guard cutter’s chances of a similar lucky break were not high, and half of them might very well be dead.

Public opinion was very much against the Coast Guard, for the rum runner had followed the traditions of the sea by rescuing and comforting the boat full of shipwrecked sailors. The incident led to the arrests and convictions of Capt. Pamphlet and his crew. The popular show of support might have been gratifying, but it did not help the Canadians’ cause.

The cheering infuriated the district immigration officer, who responded by jailing the Pescawah’s crew and throwing everything he had at the men … including a charge of entering port without inspection and failure to carry the proper entry visa. This, of course, was ironic, since the men had entered port under arrest, (which goes to the axiom “no good deed goes unpunished”).

If you’ve lived on the river for any length of time as this writer has, you too will hear the stories from old ‘River Rats’ about the floating home next to yours or just down the dock that was once occupied by a rum runner. Or in my case, about the floating home I once lived in, which had been “A House of the Rising Sun” during WWII, or so the ‘River Rats’ who still pry our waterways, tell me.