By Jim Farrell

Editor: And now the first of the story.

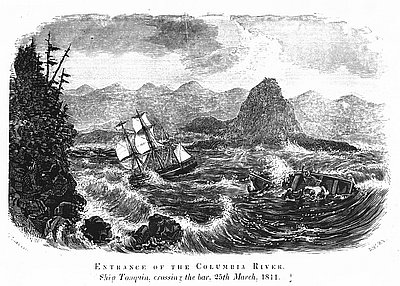

The Columbia River Bar is reputed to be the most dangerous bar crossing in the world. After crossing, it more times than I care to count, I definitely agree. Even with the now well-marked channel, GPS, and a Coast Guard station right there, it can be a terrifying trip when the tide is ebbing fast. At ebb tide, the marker buoys are forced underwater by the raging water escaping the Columbia River at 260,000 cubic feet per second, as it meets the Pacific Ocean. When the river meets the ocean, there can be waves reaching 20 to 30 feet or more depending on the wind direction of 40’ and 50’ or more, pushing against the Columbia River outflow. Then again, the Bar (Editor note… Bar is capitalized because of the danger of crossing it) can be as calm as a lake at slack tide…sometimes.

Given all that we now have that aids the navigator, I can only marvel at the grit and fortitude of what it would have taken to cross the bar over 211 years ago, when in March of that year, John Jacob Astor’s three-masted ship Tonquin attempted to cross the Bar. Astor and his partners bought the 10 gun, 290-ton vessel on August 23, 1810, for $37, 860 or $378,000 in today’s dollar. They outfitted it with trade goods and materials to build the trading post in Astoria for the Pacific Fur Company, a subsidiary of Astor’s American Fur Company.

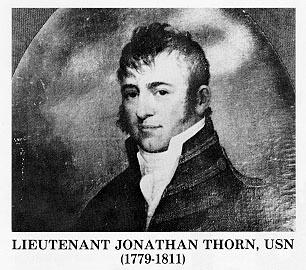

The Tonquin was captained by 32-year-old Jonathan Thorn, who was at the time a lieutenant in the United States Navy. He was a thoroughly experienced seaman and a skilled and practiced navigator who was aboard the Intrepid six years before when Stephen Decatur put the captured US frigate, Philadelphia, to flames during the first Barbary War. Thorn distinguished himself in the subsequent gunboat fighting at Tripoli, and had received special commendation by Commodore Preble. Thorn was given a leave of absence from the nave to command the

Tonquin.

Among the passengers were four partners: Alexander McKay, Duncan McDougall, and David Stuart, along with his nephew, Robert. (An interesting sidebar; McKay was married to Marquerite Wadin who later married Dr. John McLoughlin following McKay’s death. She’s buried in Oregon City alongside of McLoughlin).

They left New York on September 8, 1810, bound for the Columbia River to drop off the supplies, men, and materials with a mixed crew of Canadians, and Americans that included two black men as crew. Given that war was looming with England over its policy of taking American crew members off US ships and forcing them to crew the English fleet, the Tonquin was escorted by the USS Constitution, where Thorn’s brother, Herman, served as an officer.

The ship was barely out of the harbor when trouble started between Captain Thorn and the Pacific Fur Company partners. A rigid authoritarian, Captain Thorn maintained absolute control and discipline over his ship, while the partners wanted to be treated as equals. Captain Thorn disliked the Canadians. He considered their clerks’ journals as secret documents. To make matters worse, he could not understand the clerks, who spoke in either French or Scots Irish (Gaelic), neither of which Thorn understood.

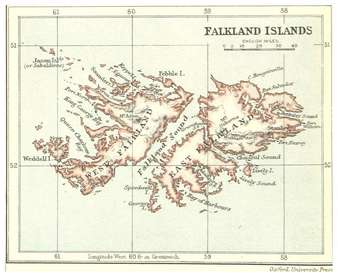

The Tonquin then made for Cape Horn, stopping at the British Falkland Islands to take on water for three days. By some accounts, the traders aboard were off hunting and didn’t hear the ship’s gun that signaled for them to return. Seeing the ship leaving, the group maned their boat and began to try to catch her. Some said that due to his dislike of the Canadians he would have left them on the Falklands, had the wind not changed, causing the Tonquin to stand to shore again.

The Tonquin’s next stop was the Sandwich Islands (Hawaii) where 24 Islanders joined the crew, 12 to man the ship and 12 who would be working at the trading post. One sailor was late getting to the ship as she was leaving, and some Islanders delivered the sailor via canoe and as they reached the ship, Thorn jumped down into the canoe and beat the man with a sugarcane stock. By all accounts, Thorn was a hard master, keeping to his own counsel.

Columbia Bar Pilot Photo

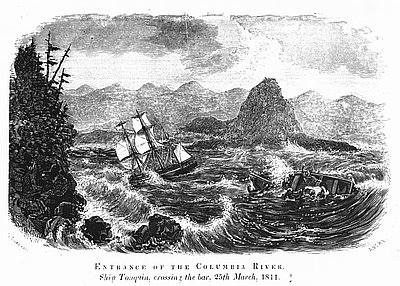

After a stormy three-week crossing with icy rain, they arrived “three leagues off the mouth of the Columbia River” on March 22, 1811. (A league is the distance a person can walk in an hour). According to witnesses, Thorn was so anxious to cross the bar in spite of a gale from the northwest that over the objection of at least two of the Pacific Fur Company partners, he ordered the longboat over the side. When the first mate, J.C. Fox also objected, Thorn replied, “Mr. Fox, if you are afraid of water, you should have remained at Boston”.

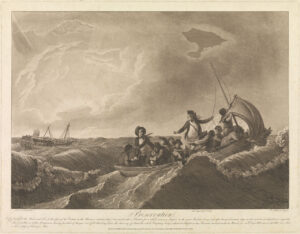

As Fox ordered his boat to be lowered, he was heard to remark, “My uncle was drowned here not many years ago, and now I’m going to lay my bones with his.” Into the boat went Mr. Fox and with four seamen to take soundings; they were never seen again. For the next two days, Thorn held the Tonquin off the bar before he attempted to dispatch the ship’s second boat, a pinnace, commanded by armorer Stephen Weeks and manned by the rigger, The sailmaker and two Hawaiians. After sounding the channel across the bar, the pinnace attempted to return, but the tide had turned and was ebbing with such force that the boat was swept pat the Tonquin “with incredible speed.” Accounts differ as to Thorn’s response, but all agree that the pinnace was last seen broadside to one of the enormous breakers that punctuated the bar, then disappeared.

Instead of heaving to or putting back out to sea in search of the pinnace, Thorn “left them to their fate”. The Tonquin struck repeatedly on the shoals, and waves broke over the deck. “Everyone who could, sprang aloft, and clung for life to the rigging…she struck again and again, and regardless of her helm, was tossed and whirled in every direction,” one of the crew later wrote. Then the wind suddenly died, leaving the ship at the mercy of the current, in the surf, n at the foot of Cape Disappointment and in danger of being dashed against the rocks.

Thorn ordered the crew to drop both anchors to counter the pull of the tide, but “darkness soon fell to add to the horrors of our predicament,” one witness stated. The tide eventually turned, with a westerly breeze sprang up to push her away from the cape’s rocky shore. The Tonquin was then able to cross the rest of the bar, and take shelter in Baker’s Bay, in the lee of the cape, just before midnight.

As for the ship’s pinnace, it was carried out to sea by the ebb tide, then was upended by an enormous wave, sweeping Aitkin and Cole (the rigger and sailmaker) into the water. Weeks later told his shipmates, “We had not passed more than three or four of the breakers before a huge one came rolling after us and broke over the stern of the boat, which engulfed us in an instant.” With the pinnace floating upside down a short distance away, Weeks watched the Hawaiians (Harry and Peter) struggling in the surf to get their clothes off, then swimming to the upturned boat. As he was clinging to a stray oar, Weeks removed his clothes also and as all three reached the boat they were able to flip it over and get enough water out to climb aboard. The tide carried them away from the shore as the light faded and the cold March night closed in.

During the night Peter died, even though Harry had laid his body over him in an attempt to keep him warm. This left Steven Weeks and Harry alive. Sculling from the stern with his salvaged oar, Weeks tried to stay beyond the roar of the breakers, hoping that they would still be in sight of shore the next morning, if they could survive the night. “I well knew that naked as I was and exposed to the rigor of the climate, I must keep active, which I did,” Weeks later reported. When daylight finally came, he could see the shore of Cape Disappointment “no great distance away”. The two men summoned their remaining strength to pass through the breakers and beach the boat.

Harry had become “so feeble and benumbed that he could not proceed,” so Weeks helped him to a sheltered spot and covered him with leaves. Weeks then discovered a beaten path that led inland, which he followed in hopes of finding help. To his amazement, he quickly reached the shore of Baker Bay to see the Tonquin floating placidly at anchor. Thorn sent a search part to find Harry, but he wasn’t where Weeks had left him. Instead, they found him early the next morning on the beach of Baker Bay “half-dead at the foot of the rocks with his feet torn and bleeding and his legs much swollen.” They immediately built a fire to warm him then transferred him to the Tonquin “where with kind attention, we managed to bring him back to life.”

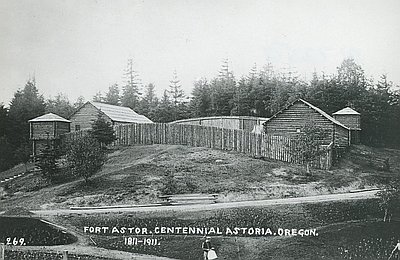

While the Tonquin was anchored in Baker Bay, Duncan McDougall and David Stuart picked Point George (Smith Point) a few miles upriver on the south shore as the place to build their “emporium of the west”. The Tonquin then moved upriver and anchored inshore, where they built a small shed for the ship’s supplies and then began clearing land for Fort Astoria. Once the work was well under way, preparations were made for Thorn’s trading cruse north, where this saga continued and ended in tragedy…

Greetings…. ;o) Just found your website/blog, so will spend some quality time reading your articles…. I’m currently reading Peter Stark’s book – Astoria thus the tie-in….

As an aside – are you the Jim Farrell who resided in Thunder Bay at one point? I worked with Gerrie Noble in the TBay Historical Society Museum – thus your name rings a bell. Thought I’d ask. Cheers. Ken Johnson, Langley Township, B.C.

Sorry Ken, I’ve never lived in Thunder Bay, however I’ve spent many years sailing from Oregon to Alaska and B.C. doing stories for various sailing magazines. Thank you for reaching out. Also, if you have any stories about the Pacific Northwest, I’d love to publish them.

Jim