By Jim Farrell

Editor note: Now for the rest of the story…

Just up the west coast of Vancouver Island, from Barkley Sound and just off the coast of Tofino lies Strawberry Island and what’s reputed in 2003 to be the anchor of Astor’s ship Tonquin. It was reported by the New York Times in a 2003 article that an old 11-by-10-foot anchor was found by a Strawberry Island diver, Rod Palm. Mr. Palm had been asked by a local crab fisherman to check why one of his crab traps had become fouled in Templar Channel, just south of Tofino. When Palm found the exposed arm of the anchor and recovered it, he became excited about the prospect that he now had the anchor of John Jacob Astor’s ship Tonquin. The question apparently is still up in the air, although the anchor is of a design used by the trading ships of the early 1800s and blue beads Mr. Palm found, were of the type used in the fur trade. It doesn’t appear to be any real proof that it is the final resting place of the Tonquin…

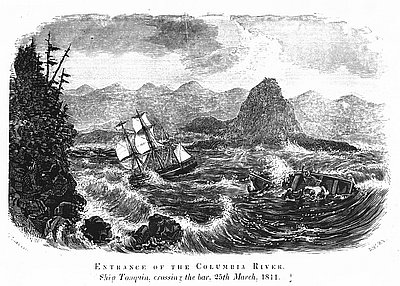

… After offloading the supplies and helping Astor’s Canadian partners get settled at the new fur trading fort we now call Astoria, Lt. Jonathan Thorn and another of Astor’s partner, Alexander McKay, left Fort Astoria and re-crossed the Columbia Bar on June 5th, 1811. Their intention (as best this writer can ascertain) was to find and meet with Aleksandr Baranov at New Archangel (Sitka) to trade supplies and barrels of gunpowder for fur skins, trading with natives as they sailed north. They were then to return to Astoria, load more fur acquired by the group of trappers that Astor had sent overland, then head for China where they’d get four to six dollars a fur. From China, they were to take on Chinese porcelain, silk etc. and return to New York.

The Astorians waited all summer for the Tonquin’s return, when rumors being passed back down the coast by natives finally reached Astoria telling of the ship being attacked and blown-up, alarming the traders. Several months after her departure, a Chehalis Indian, named Lamanse, wandered into Astoria with a terrible story of the appalling disaster.

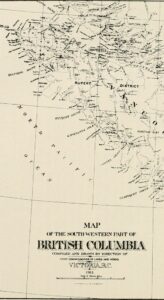

The Tonquin made her way up the coast, Thorn buying furs as he could. At one of her stops at Grays Harbor, an Indian was engaged as interpreter. About the middle of June, the Tonquin entered Clayoquot Sound. There she anchored before a large Tla-o-qui-aht Indian village. It seems that it wasn’t until two years later when the Quinault interpreter, Josechal, who had been part of the crew, returned to the outpost and relayed his version of the story. (Keep in mind as I have that this saga reaches us as second and third hand stories of the Astoria fur traders. Astor also hired renowned author, Washington Irving of Sleepy Hollow and Rip Van Winkle fame, to write Astoria, the story of his western empire).

Some say that Thorn should have known that Wickaninnish, the local chief, and other Tla-o-qui-aht peoples already had serious grievances with the Americans. Just eight years before in Nootka Sound the trading ship Boston had been overrun by Nuu-chah-nulth and their chief, Maquinna, where all were killed except the armorer John Jewitt and another, who were held captive for two years.

But given Thorn’s personality and given the way he treated his crew and the Canadian traders, it wasn’t a stretch to see that he felt only the serenest contempt for the Indians., Or even if he had understood that the native relationships, up and down the coast, relied on trade. Meaning that if you wanted to hunt, fish or even take a tree for a mast, in their territory, a trade was required. Not too unlike today, just try to take a tree of Warehouser Lumber Co’s.

Had he followed Astor’s instructions, not to let any more than a few natives aboard at one time for trade and treating the First Nations peoples that he encountered as trading partners, instead as savages, what followed, need not have happened. It was also known among the “Boston Traders” that Wickaninnish and the Tla-o-qui-aht had attempted to purchase armed vessels from other traders and even paid a substantial down payment in furs for a vessel to be built in Boston. However, due to treachery and bad luck, they were thwarted in that attempt and then attempted to take a few vessels by force. The “Boston Traders” in retaliation for one attempt, set fire to the Tla-o-qui-aht’s principal village of Opitsat.

To add insult to injury, the year before Thorn and the Tonquin left the Columbia, the captain of the “Boston Trader’s” ship Mercury, negotiated a contract with Wickaninnish. It was agreed that he would take on board a dozen or so Tla-o-qui-aht hunters to join him on an extended seal and sea otter hunt off the coast of California, where afterward they would be returned to Clayoquot Sound. Instead, honoring the contract, Mercury’s captain marooned the Tla-o-qui-aht on California’s Farallon Islands. Most of the Tla-o-qui-aht would succumb to starvation or even murder at the hands of other First Nations they encountered along the way home.

This was the environment that Lt. Thorn sailed the Tonquin into. What actually took place in the cold waters off Clayoquot Sound we have to rely on second and third hand stories, as the only survivor who had been aboard the Tonquin, was the Quinault interpreter, Josechal. It has been written that he escaped the massacre because he was married to a Tla-o-qui-aht woman.

According to Washington Irving and Astor, the Tonquin arrived off Wickaninnish’s village late in the day and anchored over the objection of Josechal, who warned Thorn of the “perfidious character of the First Nation peoples on the part of the coast”. Despite the warning, McKay and others went ashore with the natives who had canoed out to the ship, leaving six of their tribe aboard for hostages.

The following morning trade began before McKay’s return to the ship, led by a shrewd old chief Nookamas, who had grown gray as he negotiated over the years with the “Boston Traders”. Thorn made an offer that he thought was fair, but Nookamas knew what fur was worth, asked for double than what was being offered. Apparently, Thorn became enraged by the conduct of a “savage,” flung the otter skin back to Nookamas, hitting him in the face, which ended the negotiations. It’s said that Nookamas made for shore in a furious passion and joined by Shewish (a son of Wickaninnish’s), vowing vengeance. When Mr. McKay returned aboard, he was informed of the events that took place while he was gone and counseled Thorn to weigh anchor. Thorn pointed to the cannon and firearms he had aboard and replied that they were more than sufficient against the savages.

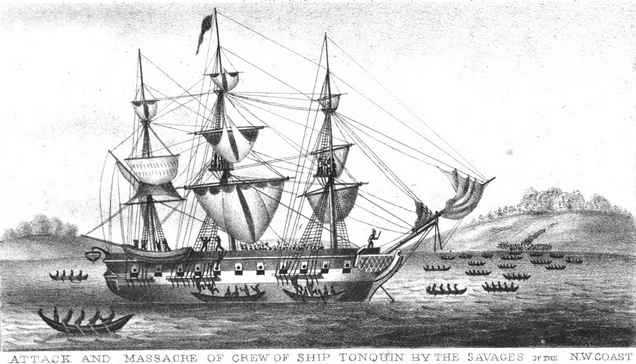

Early the following morning, Shewish and maybe twenty natives approached the ship in a canoe, making motions that they were willing to trade. As Campaign Thorn and McKay were still asleep, the officer of the watch allowed the natives aboard to trade, having no order to the contrary. These natives were followed by others in other canoes and began clambering aboard. The officer of the watch now became alarmed and called McKay and Thorn on deck. Me. McKay urged the captain to weigh anchor and set sail, whereas Thorn ordered the sails loosened and the anchor up. Just as Thorn ordered the natives off the ship, weapons from under their short mantles of skin and set upon the unarmed crew. In the fighting that ensued, four crew members and a wounded ship’s clerk, Lewis, made it below to firearms and returned to the deck and opened fire on the natives in effect clearing the ship. According to the second-hand stories, the First Nation people didn’t venture toward the ship that night. During the night, the remaining crew decided to take one of the shops boats and make for the Columbia River, as they felt they couldn’t slip anchor and sail out of the bay with the wind against them. Mr. Lewis on the other hand knew that he couldn’t make it due to his wounds and stayed abroad.

The next morning, the Tla-o-qui-aht cautiously approached the ship and, deeming it abandoned, began to return aboard. As the ship filled with natives and was surrounded by numerous canoes, the Tonquin exploded, filling the bay with ship debris and well over a hundred broken bodies. It stands to reason that Mr. Lewis set the ship’s power magazine at a time that did the most damage to the natives, although there’s no way to ascertain the truth of the matter.

The four crew members who had escaped the carnage, had been driven ashore further down the coast, were captured and returned to the village where it’s certain that they met their deaths.

Keep in mind that it was a full two years before the interpreter, Josechal’s (Lamazee) story, reached Astoria, and I’m fairly certain the story was told to explain this survival in a way that Astor’s traders found believable. In Irving’s writing of the book ‘Astoria’, he had to rely on the reports filed by Astor’s partners and the book wasn’t published until 1836, a full 25 years later. In this writer’s mind, maybe the truth lies somewhere between the fur trader’s version of events and the oral history of the Tla-o-qui-aht…

What really amazes me here is that there seems to be no mention of another ship called the Boston that was attacked had its crew killed just anbout 10 miles away from the Tonquin sight.

Hi John,

The vessel Boston is another story to tell, as John R. Jewitt, was the ship’s armourer, and spent almost three years as a slave by the chief of Yuquot, a village in Nootka sound. A few months following his rescue in 1805, Jewitt published a 48 page booklet “A Journal Kept at Nootka Sound” about his captivity. That story is still waiting for me to add to the website. As always, the editor would welcome an article for publication.

Jim