By Jim Farrell

Kq-a~-la~-o`k, meaning “a good place to land”, in the Salishan language the Quinault natives used, and then corrupted by European’s to Kalaloch, when they arrived. The beach was part of the coastal highway the Quinault, Quilcute, Hoh, Makah and other Pacific Northwest natives’ tribes used for trade, all up and down the coast, from the Columbia River (or as the Chinookan people called it, ‘Wimahl’ Great River) to Alaska. The beach it ‘self at low tide was used as a traffic corridor between villages of natives who lived between the Hoh River and Willapa Bay.

Now days, Kalaloch has become a get-a-way destination for campers in ocean side campsites or even staying at Kalaloch Lodge, which is perched on a bluff where Kalaloch Creek flows gradually into the driftwood-lined beaches of the Pacific Ocean. Kalaloch Lodge is the only lodge in Olympic National Park that’s on the coast. It’s also a gateway to the Hoe River Rain Forest and Lake Quinault.

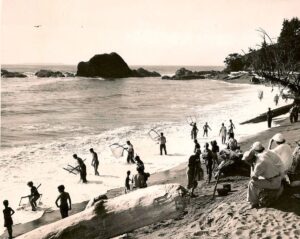

However, as this writer remembers Kalaloch Beach along with Ruby Beach, further up the coast, was the stretch of beach where those of us who lived on the “West End” of the Olympic Peninsula’s Clallam County, would either dig for razor clams or await the smelt that ran each year. It was where we would meet with our smelt nets, buckets, and picnic baskets that the women folk would pack potluck meals for one and all. Most of the smelters were loggers or fisherman and people who made what living they could in that wet, unforgiving area.

In early April, Dad would load up the old car that was held together with bailing wire, with mom and my three older sisters and me. Along with our little logger caravan from Joyce, were the Nowlin’s, their three kids, Pete Barns along with his kids, and a couple more carloads of neighbors, whose names I can’t remember.

Fires were started on the beach as the women folk laid out their potluck offerings before heading into the surf with their husbands. As for the kids, well, we did what kids do. Generally, get in the way, build sandcastles, explore the beach, and chase each other, then run back to the fires to get warm. The men folk would get the dip nets that were tied to the top of the cars, wade into the serf and begin to throw out the long poles with their rectangle shaped nets, then drag them back and dump the smelt into buckets.

It became the job of kids who weren’t running around being crazy, to hold the buckets for the smelt fishermen and run them back up the beach where they were dumped into larger tubs. This was the job that this seven-year-old writer was assigned to. Well, until I was wading at my dad’s side waiting for him to dump his net full of smelt into the half full bucket, when the riptide knocked me off my feet and began to take me out to sea! Down under the waves I went with the bucket still in my hand, when my dad reached down and grabbed me by my overalls spenders and yelled at me, “hold the bucket up Jamie!” Apparently, he didn’t want to lose the smelt in it. He then pulled me along with the bucket and the net all back to shore, where I was settled by the fire with a blanket around me.

My 4’6” mom on the other hand, along with Pete’s wife, who was also on the short side, would wade out in the serf, only to have it break over them, and the slimy critters would go down their blouses, until they got the idea to tie the bottom of the blouse and trap the smelt, then head back up the beach and dump them into the tubs.

That was the year there were so many smelt running, that when the tubs were filled to the point of overflowing, the families donated extra “pedal pushers” and “bib overalls” (that had been packed for the kids when they got wet), had their legs tied together, and filled them with the little slimy, silver fish. Of course, that was toward the end of the outing, as having that many over the legal limit was sure to result in a heavy fine or even a little time visiting the Clallam County’s jail. There was a limit of how many pounds each fisherman could take, but the community had a good idea when the state game wardens weren’t around and when they were.

You may ask why anyone would take that many fish at one time, but if you were a logger in the 1950s, you would be lucky to work six or eight months a year, as during the summer when there was extreme fire danger, the forests could be set ablaze by a single spark of a chain saw or other human cause. Many times, toward the end of summer, the loggers would have what was called “Hoot Owl conditions” when they’d leave home long before daylight to be in the forest, and head for home around 10:00 or 11:00 AM. During the winter, the snow was too deep, and they couldn’t get “back into the woods”. Needless to say, many families on the “West End” of Olympic Peninsula depended on what they could grow, raise, catch and/or shoot, then can or freeze it. There were many families who tried to live on 18 to 20 bucks a week of unemployment insurance and the occasional government’s surplus food of cheese and powered milk.

The trip is well worth it as it doesn’t take huge RVs to enjoy, as there are many campsites for tents and smaller RV’s. The sunsets all along the coast (when it isn’t raining) are stunning and sites, like the ‘Tree of Life’ at Kalaloch, are not to be missed. It’s also called, The Runaway Tree, and simply, the Kalaloch Tree. The tree is a Sitka spruce, the largest type of spruce. It’s literally hanging by a limb. As seen in the photos, the massive tree clings to its parting coastal bluff by winding thick roots. Underneath the webbed roots of the Kalaloch Tree is the Tree Root Cave. Inside, a stream falls into the cave and flows out into the ocean. It’s this stream that washes out the soil underneath the roots every year. Many questions how the tree continues to grow, and the leaves continue to stay green.

If you’re planning to make a trip to the west-side of the Olympic National Park, be sure to check and make your plans early, as the campgrounds of Kalaloch, along the Hoe River and other sites from Lake Crescent to Hoquiam, tend to reserve early.