(some true, some…well not so)

By Jim Farrell

Thinking of doing the “Inside Passage” to Alaska and maybe all the way to Skagway and on, this year? There are those who just want to take a cruse trip with little or no trouble on their part. All their meals are prepared, drinks flow freely and there are plenty of people to strike up friendships with. These can cost as little as around $500.00 per person to as much as $9000.00, depending on which cruse lines and what adventure that they’re looking for. But even though many of the cruse lines have people aboard telling about the geography, and some well known stories, they’ll miss hearing of the legends and true stories of those who eke out a living all along the Inside Passage, first hand.

Then there are those who’d like to take their RV on the Alaskan Ferry system on Ferries like the Malaspina (Russ Farrell did the carpentry in her when they split her in half adding 50′ to her length, [Dad’s blog… Waterfront Working) and get off at different ports to spend time exploring and finally travel back south on the Alaska Highway. While looking into this latter option, this writer priced it out by using the Alaska Ferry system, leaving from Haines or Skagway, traveling to Denali and home via the Alaskan Highway, to be about $13,000.00 for us in our 21′, Harvey the Arrr…vy, Roadtreck RV. Now, this group of adventures will definitely get a lot more out of their trip, and it may still be in the back of this writer’s mind, but…

… With one hell of a lot of planning, time available and a damn good boat, a trip of a lifetime. 28,000 miles of sailing those waters with my wife, Becky in our sailing-vessel, Autumn Daze, has taught this writer to first and foremost, know your vessel, in and out. Be forewarned that you’ll be from hours or even days away from help due to cell phone or marine radio, both with signals being “line of sight” which doesn’t work too well when you’re sailing in and around mountains, (though strangely enough, We were able many times to sail to the middle of some straits and pick up a signal). Be sure to pack enough spare parts, tools, and paper charts (hey, electronics do fail, at the worst possible time). Know the difference between tides and tidal currents. It’s not unheard of, boats setting their anchor when they see 15’ under the keel and wake up in middle of the night, high and dry. As you approach any one of the many narrows that you’ll pass through, be very aware of timing, as you could be either going through at 14 knots (depending on which narrows) above your boat speed (Seymour Narrows) or bucking the same 14 knots of current. Add the weather and…

…well, enough about that, for if you’re even thinking about such a voyage, you’ll have already been busy learning all you can from magazines, books and the internet to make sure you and your crew have a safe trip.

When you finally stow your anchor and head north, the many stories you have read about those ‘who-came-before’, come to life as you sail through the many small, out-of-the-way villages and towns. Some long in decay, while others struggle to keep up with the changing world around them, each with a story, that deserves to be remembered.

Stories like the “Hip-boot navy” of World War 2, when Canada had their fishing fleet paint their boats gray, and they patrolled the west coast of BC, all-the-while fishing. Or the story of the “Spirit Bear” who for many years was considered a legend of the Gitg’at and Kitasoo Native Peoples, but are real and endangered. Their range is from Princess Royal Island to Prince Rupert Island, Terrace and East Hazelton. Of course, there are the stories of those who still live along Johnstone Strait, like Ron, who across the inlet from Port Neville that tells the story of his three wives. The first died (according to him) of mushroom poisoning, the second, well, she also died of mushroom poisoning and the third, my have caught on before she ate any mushrooms, and decided that she didn’t really want to live in such a remote area. Now his story could be real, or maybe, just maybe, he just liked to tell tall stories, who knows?

In almost every inlet, bay and village that you’ll sail through, there are stories that the local natives can’t wait to share, all the way to the farthest point north on the “Inside Passage” to Skagway, where you’ll find; “There are strange things done in the midnight sun, by the men who toil for gold” (Robert Service).

The stories of the Klondikers are of hardship or even tragic events, such as the Chilkoot Pass avalanche on Palm Sunday, in 1898 as the “Stampeders” tried to make their way up the pass to the gold fields of the Klondike. In their rush to gain the fields in early spring, a few stampeders ignored the danger signs of avalanches, even after the Tlingit and Tagish native packers, refused to work the trail. This was their land, and they knew how deadly the conditions had become that spring day. The citizens of Dyea had already dug out twenty odd stampeders earlier that morning, but as well over another 150 finally realized their danger and turned back down the pass following more rumbling from the ‘Scales’, the snowpack broke loose burying over 70 under 50’ of snow.

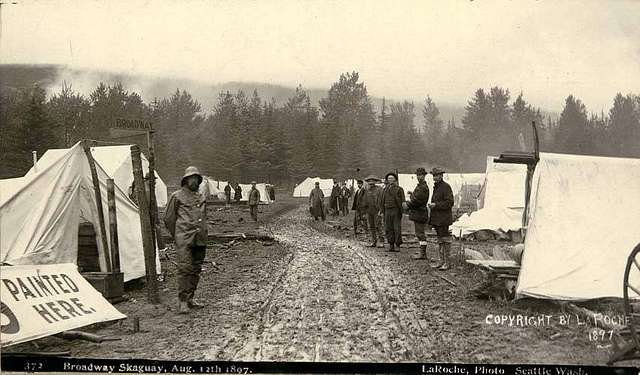

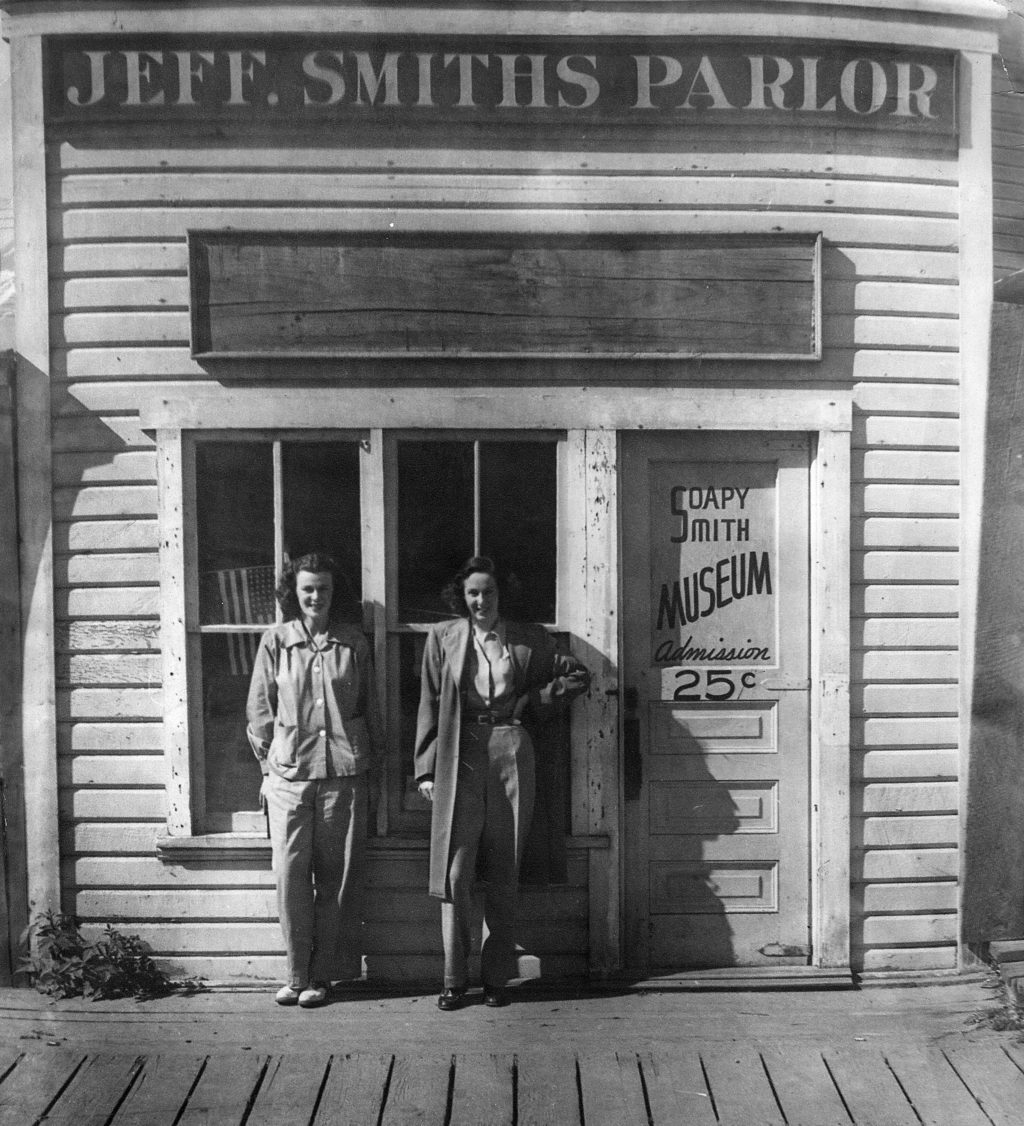

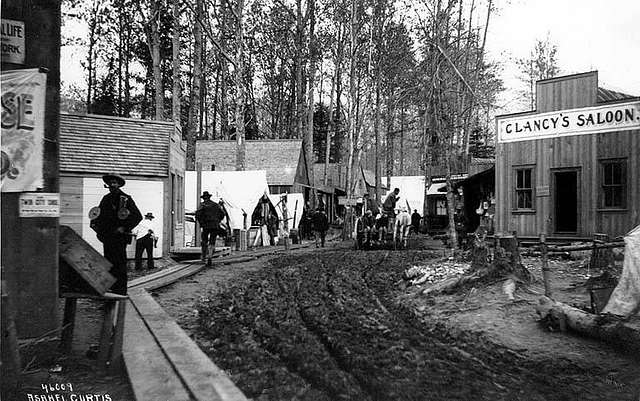

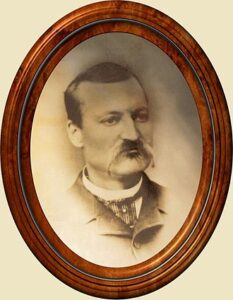

Even before the hardships of packing up the Chilkoot Pass the 2000 lbs. of supplies that the RCMP required to enter Canada each Klondiker have, in 1897 an infamous historical character with the nickname of, “Soapy Smith” appeared in Skagway with his gang of confidence men and all-around scoundrels, leaving a trail of swindles and men with empty pockets.

Jefferson “Soapy” Smith became infamously known for his soap swindle in Colorado, where victims were taken. He set up his tripe and keister (stand and suitcase) on the sidewalk and began a spiel on the wonders of the soap he was selling. In order to increase sales, he offered cash prizes in several of the soap packages. He would begin to wrap up the cakes of soap with plain paper. Every couple of bars he would show the crowd some currency ranging from $1 to $100 ($100 would equal almost $3,000 in today’s money) and wrap the bill in with the soap. He then mixed the wrapped packages together and offered them up for sale. The price for the soap ranged anywhere from $1 to $5.

Unknown to his victims, mixed in with the crowd were members of his gang. Only these shills were fortunate in picking out the lucky bars of soap that contained cash. Once opening the package and finding money inside the shill would let out a holler of celebration and begin to mingle through the crowd letting everyone within a block or two away know that they had beat the soap salesman at his own game. It was all a swindle. There was no money in the soap packages to win.

Jeff (as he preferred to be called) and his gang expanded their criminal expire to the point that he ran the underworld in and around Denver and when he couldn’t bribe the cops and city officials any longer, left for Alaska and new picking grounds. Once in Skagway he and his gang became the de facto government. They ran a telegraph line a few blocks from his saloon to downtown and as stampers debarked the boats, they’d send a telegraph home to let their families know of their safe arrival. A telegram would soon follow asking for money, and the Klondiker would give Soapy money to send home. Little did the fleeced man realize, that there were no telegraph lines leaving Skagway and wouldn’t be until well into the 1900s.

The gang ran the gambling and prostitution business and when they couldn’t separate a mark from his money one way, of course there were dark alleys where the stampers were separated from their cash, another way. All was going the gang’s way as the city reached over 15,000 full time residents and one too many Klondikers had been conked on his head and relieved of his gold dust. It was then that the recently formed the “Committee of One Hundred and One” decided to take on the problem of Soapy and his gang and posted a notice:

WARNING

A warning to the wise should be sufficient. All confidence sharks, bunco men, and sure thing men, and all other objectionable characters are notified to leave Skagway and the White Pass Road immediately and to remain away. Failure to comply with this warning will be followed by prompt action.

(Signed) Committee of One Hundred and One.

Not to be dismissed, Soapy posted his own notice:

PUBLIC WARNING

The body of men styling themselves the Committee of One Hundred and One are hereby notified that any overt act committed by them will be promptly met by the law-abiding citizens of Skagway, and each member and their property will be held responsible for any unlawful act on their part. The Law and Order Committee of Three Hundred and Seventeen will see that justice is dealt out to the fullest extent and no blackmailers or vigilantes will be tolerated.

(Signed) Law and Order Committee of three Hundred and Seventeen.

(strangely the address of his saloon)

As the Committee of 101 decided to meet at the docks and had set out armed guards, Soapy who had been drinking, determined to settle the matter once and for all with his .44/40-caliber Model 1892 Winchester rifle, stormed up the boardwalk and only Frank Reid, the city engineer, stood in his path. Smith came to an abrupt halt and swung his rifle at Reid, who caught the rifle barrel with his left hand, pushed it aside and, with his right hand, drew a revolver and squeezed the trigger. Its first cartridge misfired. Grasping his rifle in both hands, Smith jabbed it into Reid’s groin and fired. Almost simultaneously, Reid snapped off a shot, fell, raised his gun and fired again. Soapy died on the wharf, while Reid dying a few days later. About half a dozen of his gang watched from the shore, realized that it was time to depart Skagway and headed for the hot springs of Tenakee to figure out what to do next.

dock

Such are the stories that are to be found in “the Land of the Midnight Sun” all along the Inside Passage.