By Jim Farrell

I have an inquisitive and adventurous nature about me that sometimes–well, a lot of the time–gets me into trouble. But sometimes I stumble upon a good story! Such was the case when I began to dig around old newspapers looking for information about the Canemah shipyards that were just above the Willamette Falls in the 1850s, until the Willamette Falls Locks were built.

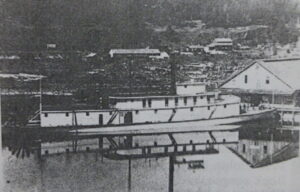

A couple of stories I found made me stop and realize how difficult it was to build the shallow-draft steamboats, used on the upper Willamette, prior to the building of the locks on the West Linn side of the falls. The steam engine and all the associated machinery had to be shipped around “The Horn” to Portland, then pulled by a team of horses from the foot of the falls to the boatyard.

One such story was reported in the Sunday Oregonian on November 11, 1900:

“It was no light undertaking in those days before the construction of the Willamette Falls locks to transfer a steamer from the upper to the lower route or vice a versa. Still, it was often found either necessary or desirable to do so and it was not the fashion in pioneer timers to be daunted by difficulty, or to hesitate in the presence of an obstacle.

A sort of basin had been built on the Oregon City side of the stream (some historical accounts have the basin on the Linn City side), abreast the cataract, and into this the boat was floated. Thence it was drawn out upon the beach and let down a skidway, by means of ropes and cables and primitive machinery, to the level below the falls. If it was to be a transfer from the lower to the upper route, the process was simply reversed.”

I found other references of sternwheelers that would wait until the ‘freshet’ (warm winds and rains of spring that cause a snow melt off). At full flood, the river rose so high that the falls disappeared under the volume of water, and the crew could float the boat down to the lower river.

Not only were the movement of goods and people up and down the Willamette and its tributaries extremely hard and demanding work, but dangerous as well. Steamships of the time were extremely susceptible to having their boilers overheat and explode–especially if the engineer didn’t keep his eye on the pressure valve, or it clogged up with sediment from the dirty river water. The most famous disaster in Oregon destroyed the 145’ side wheeler Gazelle built in 1854 in Linn City (West Linn) by the Willamette Falls Milling and Transportation Company.

From the Oregonian, April 8th, 1854:

“TERRIBLE ACCIDENT!!!

Steamboat Gazelle, blown up this morning at Canemah! Over twenty killed and twenty-five wounded!

After a portion of our edition had been worked off this morning, the startling news reached our city of the explosion of the Willamette Falls Co.’s new steamer Gazelle. We stopped the press and dispatched a messenger to the scene of this melancholy disaster, for the purpose of obtaining the particulars. Our reporter gathered the following facts:

The Willamette Falls Co.’s new steamer Gazelle left her wharf this morning at half past six o’clock, and had just landed at Canemah, at fifteen minutes before seven, when a terrible explosion of her boilers took place, blowing up her upper works, cabin and after part, which were literally torn to pieces.”

The Gazelle had only been working on the upper Willamette for about three weeks and was on the regular run upstream from Canemah. It departed at 7:00 am on Tuesday and Friday of each week and stopped at Butteville, Champoeg, Weston, Fairfield, Salem, Cincinnati, Independence, Washington, Albany and Corvallis.

According to the reports, the Gazelle had run across the river briefly to pick up cargo from the steamer Willamette and apparently the chief engineer, Tonie, under company pressure to have a quick turnaround, kept the steam safety valve tied down. With the escape valve howling, the engineer Tonie was seen running away from the Gazelle while the passengers were embarking.

The explosion killed twenty-four and injured another twenty-five. Many ended in the water, where a massive effort of the Willamette’s crew and people on shore attempted to pull them out of the fast-moving river before they reached the falls. As with many wrecked vessels in that era, the remains of the Gazelle were salvaged and rebuilt, first as a barge called Sarah Hoyt, and later she received a new boiler and was renamed the Señorita.

The Señorita was then used to carry troops, horses and army stores from Portland to Fort Vancouver and the army post at the Cascade rapids on the Columbia. About 100 yards from the Willamette Falls lookout on Hwy 99 just south of Oregon City, there’s a plaque that commemorates the explosion of the Gazelle.

Up and down the rivers of Oregon one may find other grave markers, such as one for Crawford Dobbins a Gazelle victim interned in the Lone Fir Cemetery in Portland, or even the stone marker found embedded in the riverbank by Charles Aubin, of the Tualatin Riverkeepers, of one of the ‘Senator’s’ victims on the banks of the Tualatin River at the end of Dollar St. in West Linn. It reads:

“Klaus Beckman killed 3 P.M. May 6, 1975, Explosion Str. (Steamer) Senator buried 133 ft. N. May 25, 1875, wife Kate, son Fred survived, 7 crewmen died 12 mi. N. Willamette R.” It should also be noted that the Beckman family were early settlers in the Wilsonville area, where their descendants are still living.

[At 2:45 p.m. on May 6, 1875, the boiler on Senator exploded. The steamer had just left its mooring at the dock of the Oregon Steamship Company, (at the foot of the Morrison Bridge) and steamed past the city front, to the foot of Alder Street, where its speed slackened in preparation for coming alongside the steamer ‘Vancouver‘, moored at the Willamette River Transportation Company wharf, where Vancouver was to transfer cargo to Senator. The stern-wheel of the Senator had just ceased to revolve when the explosion occurred. (Oregonian, May 7th 1875)]

The history of life around the second-largest falls in the United States is filled with many such tragedies, but it’s also a place where there have been many happy events. Millions of people have viewed the falls in all their natural wonder. Even now, the cities of Oregon City and West Linn, along with Clackamas County and the Ground Round tribe, who have renamed their property, ‘Tumwata Village’, (Tumwata means waterfall in the Chinook Jargon) in are remembering the history and making plans to make the falls more accessible for the public to enjoy.

(Old photos, courtesy of the Oregon Historical Society, and Clackamas County Historical Society.)