An Encampment, Naval Base, Coast Guard Station, Lighthouse Service, and Safe Haven

Learning to sail on the Columbia River has given many generations of NW sailors the skills and confidence to cross the Columbia River Bar and head north, south or even west. Here is where we’ve learned about the Rules of the road; Red light returning, Tonnage has right of way, a vessel engaged in fishing has right of way, (sorry, fishing from a small fishing sled or boat does not constitute “a vessel engaged in fishing”, which brings us back to “Tonnage has right of way”, do you really want to take on a tanker?) navigation lights and other “Inland Navigation Rules”. Best not to forget sail handling in winds ranging up to 50mpg or even above, if you and your crew are unfortunate enough not to find a safe haven in time.

The Columbia and its many tributaries, bays, and islands offer many “safe havens” to drop your ground tackle where you’ll learn about which type of anchors drag in different types of seabed and how to put out enough anchor rode so you don’t smash into another boat or run aground. It’s here on the Columbia that you put to good use what you’ve learned from books like “Chapman’s, Annapolis Book of Seamanship, Bowditch and even Nigel Calder’s, Cruising Handbook”. The Columbia is where you may learn about “running aground” and how to kedge yourself off when you forget the old adage, “never sail where seagulls are standing”. Its also where you’ll learn that “sailing is really a matter of lurching from one crisis to the next”.

Since the days of Lewis and Clark, and even before the appearance Robert Gray and the Columbia Rediviva in 1792, the lower Columbia River was used by the Native Americans for food, clothing, shelter, trade and transportation. On November 27th, 1805 Lewis and Clark happened upon one of many “safe havens” that the Indians called “Kekemar〈qu〉ke” Lewis and Clark called it “Point William”, but we know it today as “Tongue Point” which was first named in 1792 by Lieutenant William Broughton of George Vancouver’s expedition. It was here that the Corps of Discovery stayed for ten days prior to their move to Fort Clatsop for the winter. From this safe haven, (even though they were subjected to rain and wind that tore into their rotting tents) the “Corps” were able to send out hunters and found deer, elk, geese and ducks that fed the sick and weary explorers.

Don’t expect to visit the campsite, as the location of the encampment is on the restricted US Coast Guard’s buoy tender Elm base, that services and maintains 115 aids to navigation along the Pacific coast, from the Oregon/California border north to the Strait of Juan de Fuca, and east in the Columbia River to Longview. The Coast Guard base also houses the Aids to Navigation team, Advanced Helicopter Rescue School, and Electrical Support Detachment. The Base has been used by the Coast Guard since 1876 when it was occupied by the Coast Guard’s predecessor, the Lighthouse Service.

But the location is visible from the Astoria Riverwalk sign and bench placed there by the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation’s Oregon Chapter, Astoria Parks and Recreation Department along with other local leaders.

Today sailors sailing down the Columbia find Tongue Point to be a peninsula, however in Lewis and Clark’s time it was an island with a narrow isthmus connecting it to the mainland. On the east side of Tongue Point is Cathlamet Bay, a well-protected anchorage that allows a skipper and his/her crew, a respite following a trip down the river or a crossing of the Columbia Bar coming off the ocean a safe haven. Many times, dockage at Astoria’s West Mooring Basin, tends to fill up in the summer months, is full and added to that, the entrance to the basin at ebb tide can be tricky as the waves are 8’-10’ or more just outside of the moorage. In Cathlamet Bay’s calmer waters allows for jumping and swimming off the boat and fishing opportunities to catch salmon or sturgeon, (https://tides4fishing.com/us/oregon/astoria-tongue-point/forecast/fishing).

It’s also the site of the old Tongue Point Naval Base that the Navy acquired from Clatsop County in 1919, following the First World War where the Navy Department intended to use it as a submarine and destroyer base. The Navy then proceeded to hydro-fill the little isthmus that separated the point using sediment from offshore dredging operations. The property apparently (this writer can’t verify if it was ever used as a submarine base) was used by the Navy in 1924 as the Navy base. Use was limited to the uplands area and some tidelands, but the property was essentially dormant until dredging and filling began in 1939 just prior to our entry in WW2 as the Navy began converting the base into a Naval Air Station for seaplanes. First for the iconic PBY Catalina’s used for coastal patrols, followed in 1944 by the more capable and larger, PBM Mariners (Patrol Bomber, Martin).

However, aircraft operations in and out of the bay proved difficult, due to the logs and other flotsam on Cathlamet Bay, which made takeoff and landing conditions hazardous. From 1943-1944 the station’s intended mission was temporarily sidetracked, when its facilities were used instead to assist the Kaiser Company in a critical shipbuilding program. This became the facility’s most significant role during WW2, as a per-commissioning & commissioning site for escort aircraft carriers (better known as “jeep flattops”) built in the big Victory shipyards in the Portland-Vancouver area.

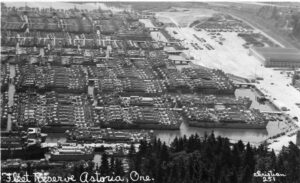

Following the war (1946-1962) the base was converted into a moorage facility for our Ready Reserve fleet of as many as 250 Liberty ships and expanded the base with eight concrete piers to accommodate the fleet. As may be expected, the storage of 250 deactivated and mothballed ships would create a massive amount of waste that needed disposed of as mothballing typically involved stripping paint, removing fuel and fluids, and repainting. The Navy’s answer to the problem was to develop a landfill on site, to depose of; waste oil, diesel fuel, machine shop wastes, building and landscape demolition debris, various oils/paints/solvents, metals, wood waste, buried drums, car engines and frames, large appliances, crockery, wire, glass, bricks and probably the kitchen sink also.

In 1962 the Navy deactivated the Navel Air Station and transferred it to the General Services Administration. In 1971 a portion of the former base was transferred to the US Dept. of Labor for the use as a Job Corps site. (Sidebar; in a recent visit to the site via land, this writer was denied access to drive through or photograph the Job Corp site without prior approval by the not too friendly guard’s supervisors. The reason the guards told me was that the Dept. of Labor was under the Dept. of Defense. This was news to me as I’m fairly certain that it’s not under the Defense Department) Subsequent property transfers included transfer of the southern portion to ODSL (Oregon Dept. of State Lands) in 1980. This transfer included the former landfill area. The post-DOD activity at the Landfill included miscellaneous disposal activity by various local business enterprises consistent with the light industrial, marine, and wood products related activities of the local area. Needless to say, the old landfill had many environmental hazards that caused the USACE (Army Corps of Engineers) to investigate and the decision was to Cap the pollution in place, which was done in 2015 by DEQ. The docks are being used today by Hyuk Maritime, a U.S. based marine transportation company that constructs and charters vessels to marine companies.

Cathlamet Bay is indeed a safe haven where you and your crew may still find peace and tranquility, as the John Day River (the coast one) empties into the bay. When one drops anchor in 22’ of water close to the islands that border on the west side of the bay (Mott and Lois Islands are part of the Lewis and Clark National Wildlife Refuge), any crisis that may have been encountered on the sail downriver or crossing the bar from the Pacific are soon laid to rest.

Now it’s time for the fishing poles to come out, swimming (in the summer) or just hanging out with friends and family over drinks and a great meal. It’s also a time to reflect on times past and try to imagine what the Army Corps of Exploration experienced and maybe even think of Tongue Point’s role during the war.

All black and white photos, courtesy of Columbia River Maritime Museum’s archives.

https://www.lighthousedigest.com/Digest/StoryPage.cfm?StoryKey=5052

You may enjoy this information. Axel Anderson was amazing, an inventor and an integral part of Tongue Point Navel/Lighthouse Depot

Looks lively. Where is it? I am looking for a map.

Astoria, Oregon, just up stream.